Empowering Math Teachers to be Culturally Responsive

[ad_1]

By: Tanaga Rodgers

The Perfect Pair…

About a year ago a former colleague of mine invited me to take part in a book study she was co-facilitating about culturally responsive teaching. The study was mostly situated around literacy instruction with a few science or math examples sprinkled throughout. However, about midway through the weekly discussions, I started making connections to my own experiences as a math teacher and started wondering what culturally responsive teaching would actually look like in math class. I approached my colleague about this and together we decided to dig in and see what we could discover.

What we found was lots of good research and theories that applied broadly but not many specific classroom examples that teachers or coaches could translate to the math classroom. At the time, both of us were former elementary teachers turned into state education agency professional development specialists. So naturally, the next step for us was to put our heads together to create a professional development series with strategies for practitioners to take and use in the classroom. With her specialty in social-emotional learning and mine in K-8 mathematics, we seemed to be the perfect pair to embark on this journey.

Culturally Responsive Teaching…in Mathematics?

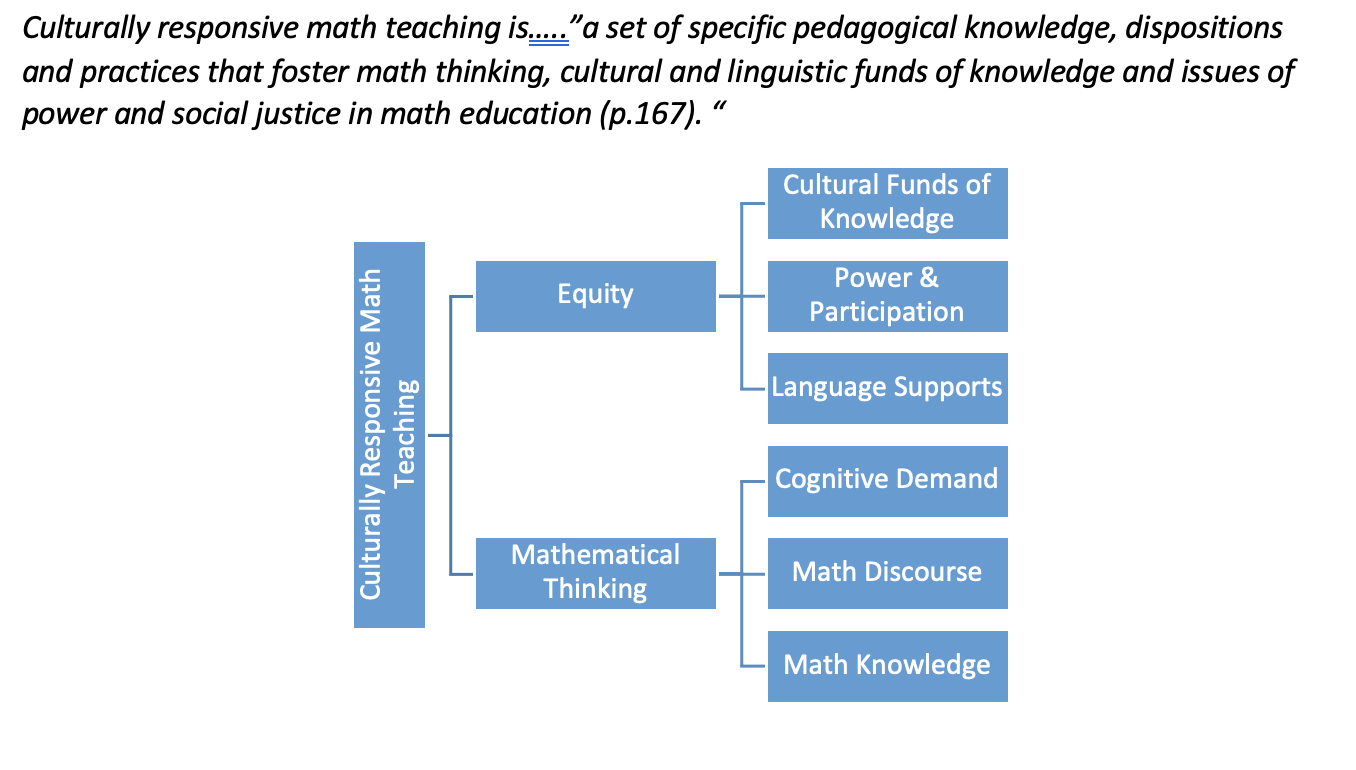

Although culturally responsive teaching has gotten much attention in recent years, most of the spotlight has been in the humanities. As such, many math educators are left in the dark about what it actually means to be culturally responsive in math class. My colleague and I started at the beginning by investigating the birth of culturally responsive math teaching. We found a digestible definition crafted just for math teachers by Aguirre & Zavala in their 2013 article entitled, Making culturally responsive mathematics teaching explicit: a lesson analysis tool. In their work, they define culturally responsive mathematics teaching, provide a conceptual framework for developing culturally responsive math teachers and share a tool that helps teachers strategically plan and reflect on their math lesson plans. Aguirre & Zavala (2013) organize culturally responsive mathematics teaching into two broad categories; equity and mathematical thinking. Each category has three dimensions that provide greater insight into how to promote equity and mathematical thinking.

In addition to Aguirre & Zavala’s lesson analysis tool, we also dug into the CEEDAR Center resources for culturally responsive education in the content areas. Their facilitator guide gave us a first look into some practical ways that teachers could begin to translate culturally responsive teaching practices into specific content areas. We merged these resources along with a few others and our own personal experiences to build a two-part series that would characterize a culturally responsive math teacher. We started with equity and named a few of the beliefs, dispositions and actions that describe each dimension.

Cultural Matters

When I first heard the phrase “cultural funds of knowledge” it felt like such a mash-up of words. I like the STEM Teaching Tools definition that simply says cultural funds of knowledge is the knowledge students gain from their family and cultural backgrounds. Culture has not historically been associated with mathematics teaching so it was important to start the professional development by clarifying why culture matters. Cultural funds of knowledge matters because it is a resource to support teaching and learning. Students are not empty vessels that need to be filled. Rather, learners bring with them funds of knowledge from their lived experiences and communities that can be used to situate content in context. This is important because as Dr. Pamela Seda & Kyndall Brown point out in their book, Choosing to See, teachers can use students’ prior experiences, strengths and background knowledge to enrich or scaffold students’ understanding of academic content while also motivating them during classroom activities. There are many ways to do this in a math classroom. It might look like students creating their own number and word problems to connect concepts they’re learning about to their lived experience. In a primary classroom, it might be selecting a read-aloud such as The Name Jar by Yangsook Choi to engage learners and serve as a springboard for reasoning mathematically about counting.

Power & Participation

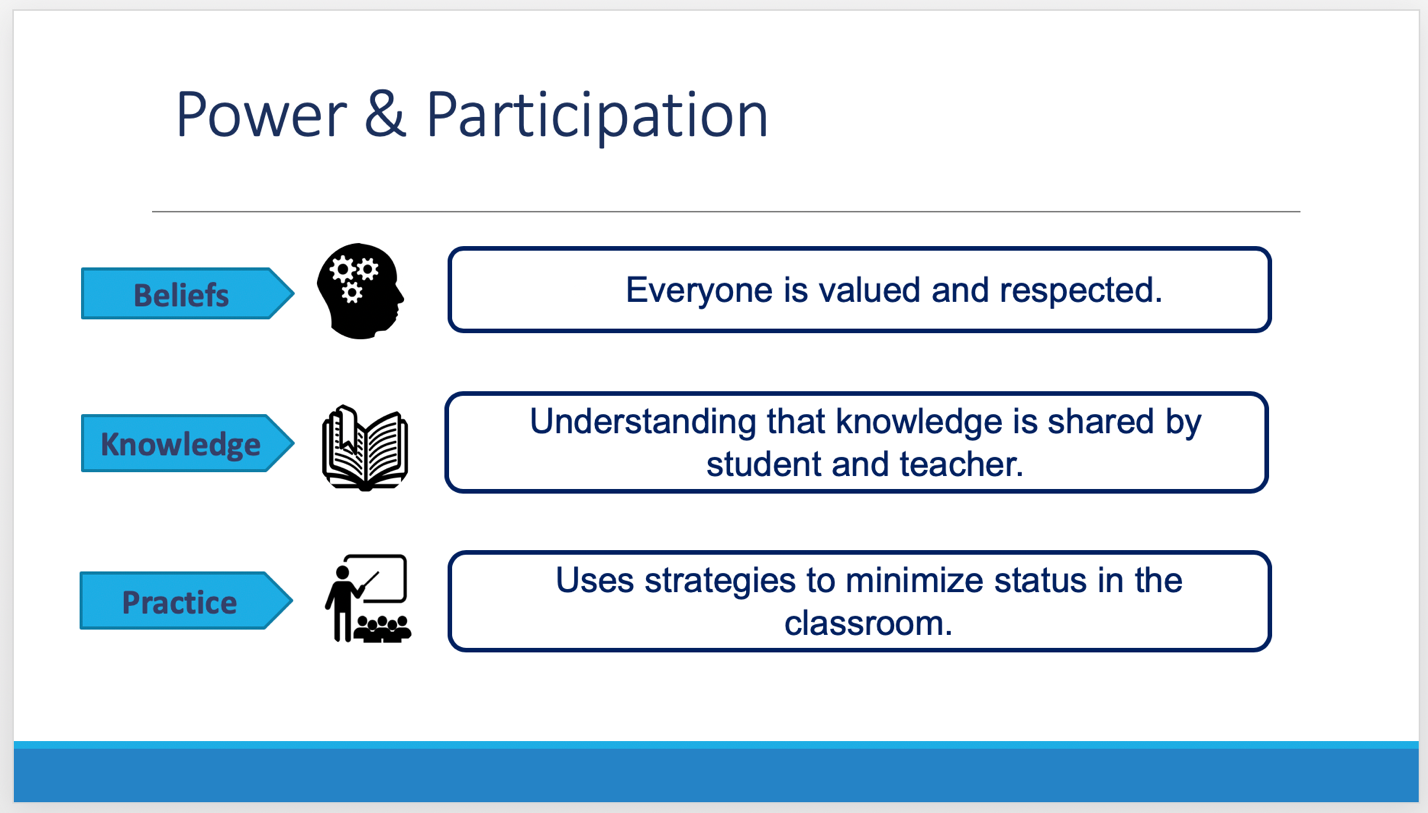

The most recent learning and brain science research tells us that our brains can’t fully participate in learning until power is balanced and our brain feels safe. Without it, we feel threatened and are in a heightened alert mode that keeps the amygdala in our brain (also known as the watchdog) constantly scanning the room for ways to stay safe. In our classrooms, that may not show up as physical threats from teachers, but threats of embarrassment/failure or lack of confidence. When your brain is consumed with trying to stay safe, it can’t process other information well. Therefore, teachers who are culturally responsive know that their job is to help students identify the math expertise that lies within themselves and around them. They also know how important it is to teach students how to leverage expertise to build their own confidence and competence in math (Seda & Brown, p.20). In a math classroom, this might look like modeling positive connections, weaving in activities that minimize status and using strategies like reciprocal teaching to take on the roles of coach and player to explore problems.. In general, students need to know that the teacher is not the sole authority and that every person brings expertise and knowledge to the classroom. This shared expertise is what makes the classroom a powerful learning space.

Language is a Tool for Learning

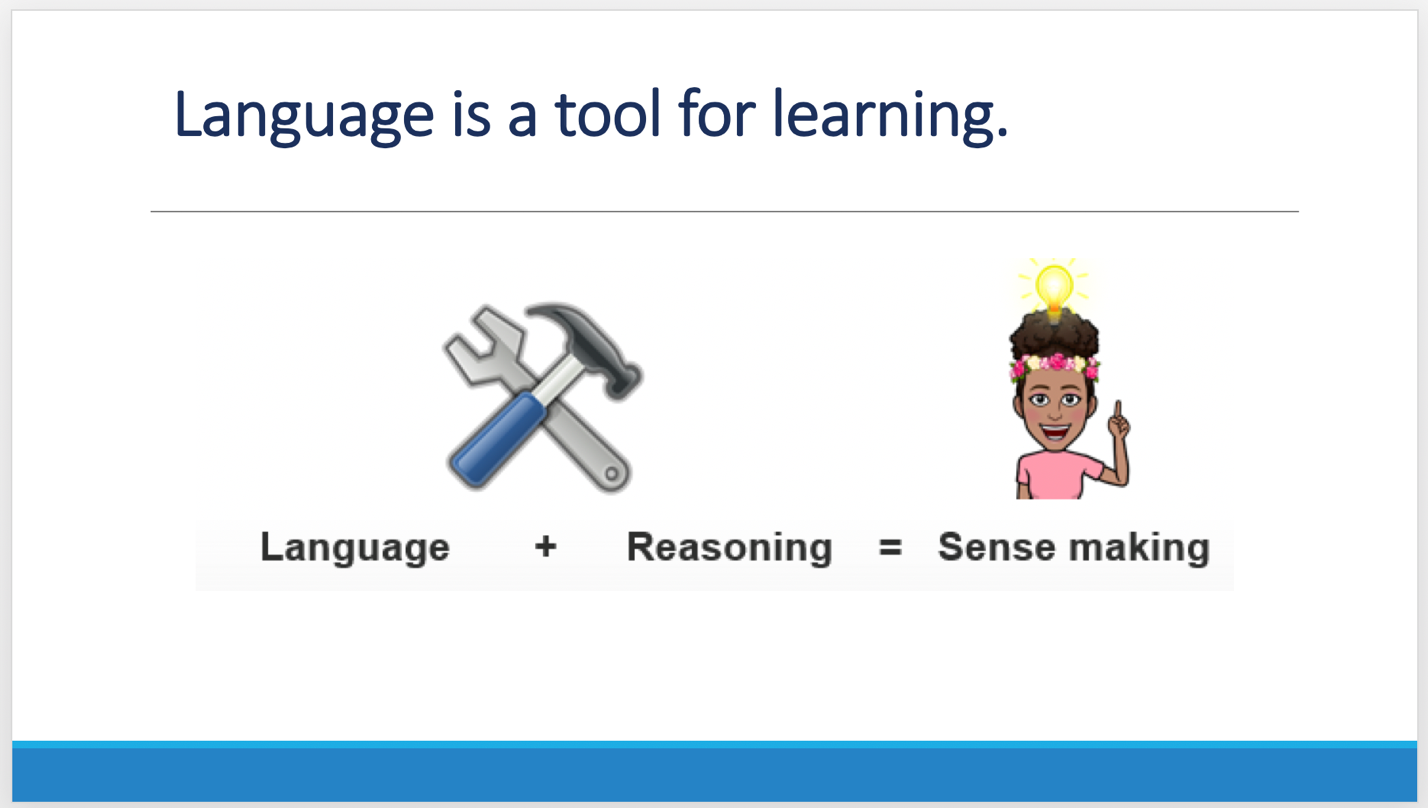

As a former elementary math teacher in a school with 80% English learners this one really hits close to home. I am most passionate about this element because in the classroom I learned first-hand that language supports benefit all learners. This is also a heavy hitter because this dimension ties closely with the other dimensions of equity. It’s closely related to power & participation and cultural funds of knowledge because language supports help all students (especially emergent bilinguals) join the conversation (participation). This element views language and the learner from an asset-based perspective and embraces students’ cultural funds of knowledge by acknowledging that language is a tool for learning. Talking about mathematics is evidence of conceptual understanding. When a student uses language to tell what the answer is or to justify a solution they are showing evidence of their understanding and thinking. When teachers support language it’s not just about supporting students in recalling academic terms. We can recall or say academic vocabulary words and not be able to use the words to express or develop our understanding, which does not serve us when learning. Beyond knowing vocabulary, in math we also use language to describe, compare, sequence, categorize, predict, summarize and explain. Communicating what you know builds and supports understanding. In math class, this might look like using sentence frames, extending wait time to students and using math talks to develop fluency and flexible thinking.

Show Them How to Fish

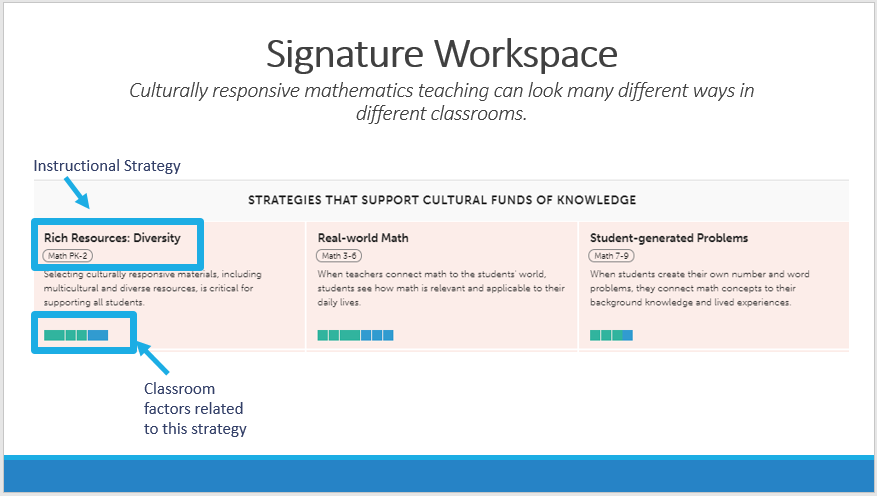

Culturally responsive math teaching can look many different ways in different classrooms. There really isn’t one size that fits all. Perhaps that’s why culturally responsive teaching can be easily overlooked in the math classroom. One concrete routine or strategy will not lead us to the solution. Therefore, the ultimate goal has to be about understanding each of the dimensions of culturally responsive math teaching well enough so that educators can artfully select instructional strategies that support their unique classroom and students. It’s like the proverb that says “If you give a man a fish, he will be hungry tomorrow. If you teach a man to fish, he will be richer forever.” In this case we are teaching educators to fish instead of giving them a fish! You can give one strategy for one student but next year they’ll have a different student. The real power is in preparing educators to assess what the needs are in their classroom and then equipping them to use a tool like the Learner Variability Navigator to identify a plethora of research-based strategies that meet the range of needs in their classroom. It’s a much more sustainable strategy because it will work year after year regardless of the range of variability in students.

To support teachers in doing this work, I created signature workspaces using Digital Promise’s Learner Variability Project’s web app, the Learner Variability Navigator, for equity and mathematical thinking. The workspaces connect research-based instructional strategies with the dimensions of culturally responsive math teaching. This tool empowers teachers to browse and select strategies based on the factors and needs of their classroom. The strategies are organized by dimension, have grade-level suggestions (although many strategies stretch across grade bands) and if you hover over the colored tiles at the bottom of each strategy you gain more insight into which specific factors that this strategy supports. Ultimately, it is our hope that with a tool like this, teachers can make connections to strategies they’ve already been using or try a new strategy with confidence that it’s specifically targeting the needs of their classroom.

Overall, introducing the Learner Variability Navigator and the Signature Workspaces to educators in my District was really well-received. I saved time at the end of the session for teachers to explore the Workspace on their own and find strategies that are relevant for their classroom. Feedback after the session indicated that teachers really appreciated having access to so many strategies and they found it useful to find strategies specifically related to the needs of their classroom! Some teachers noted in the after-session comments that they bookmarked the strategies and they plan to use the resource in the future.

Tanaga Rodgers is the LVP Practitioner Advisory Board member and math professional development specialist.

[ad_2]

Source link